Gathering

By: Arlene Shechet

Download PDF

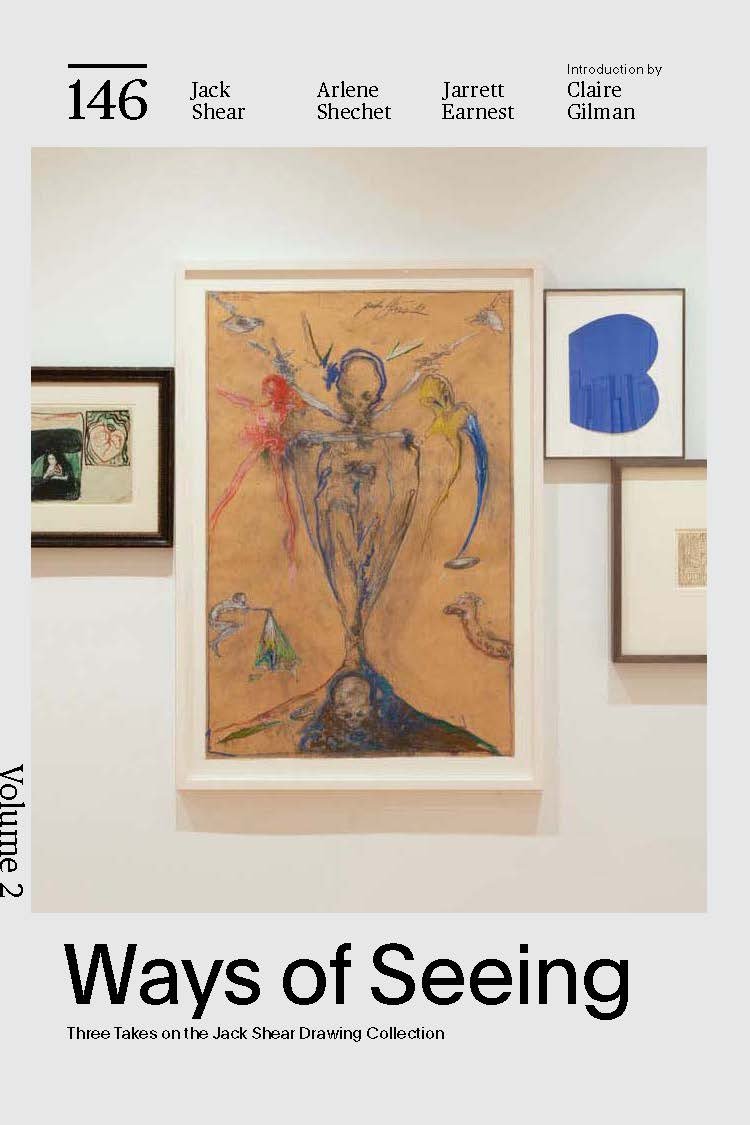

Drawings present unmediated evidence of the artist’s hand and 43 mind. They stem from an intimate practice whose tools and materials are limited. They are essentially records of the body: of being alive. As surfaces that bear the rawest marks of one’s hand, drawings are by nature intimate objects that remind us of the importance of touch. Since I conceived this show at the height of a pandemic that necessitated isolation from others, this issue of touch had double weight for me. I knew the drawings alone could stimulate an awareness of one’s body. But as a sculptor, I also knew the importance of space in shaping a viewing experience. How and where one stands in relation to an artwork is integral to how that artwork inherits meaning: how it is seen. Pulling out the drawings’ greatest potential meant connecting them to something outside of their own contours while allowing each one to independently hold its own. I wanted to play with the traditional viewing height and distance that one experiences in a gallery and have the room accommodate various body positions, inviting people to linger, have conversations, and possibly even sit together after months of being apart.

In contrast to the intimacy of the drawings, the space of

The Drawing Center has a large central volume that can feel cavernous. As a sculptor, I was sensitive to this. Creating horizontal lines to !ll the space and reach out to the walls would knit the room together. What could those lines be? Low-lying sculptures that would not interfere with viewing the drawings but would enhance the pleasure of experiencing the art. This connective tissue would eventually take the form of a quartet of hand-carved benches made from single logs of white oak. The massive nature of those bestial logs anchored and grounded the space and also provided a canvas for me to carve my own lines that played o those of the works in Jack Shear’s collection. These horizontal structures also spoke to the #uted columns (the architectural equivalent of trees) in the main gallery of The Drawing Center. From a functional point of view, and given that the show opened as winter descended on New York, the benches gave people a place to gather and spend time with the work and with each other. [FIG. X]

In planning the show, I realized I needed to paint as well as carve. Seeing a show of Giorgio Morandi’s paintings at David Zwirner gallery made me conscious of space in a new way: all the forms are compacted, enclosed, grounded. He eliminated the space between the vessels and created a divided ground for them to live in. I wanted to carry this sensation to The Drawing Center, creating a space that would hold you close while looking and make you completely aware of your own presence [FIG X].

I took note of Morandi’s use of the horizon line to divide his compositions. Inspired, I decided to hand paint the lower register of the walls, dividing them into two unequal areas using lightly modulated earth tones, in order to create a palette and texture that could hold and unite the disparate elements of the show. I wanted to create a kind of architectural landscape on the walls within which I could play with the hanging of the artworks. The paint was brushed on by hand so that the color was not opaque or uniform, conveying the feeling of human touch. Morandi’s touch is so potent, and this same impression was re#ected on the walls with brighter patches where the paint is thinner and the white wall shows through—the uneven work of the hand lending an overall dynamism.

Drawings reveal the imperfection of being human, complete 50 with a wobbly hand that exerts irregular pressure across a

surface. In a few drawing selections and placements, I pulled this unevenness out explicitly. The Jim Nutt Oh Look! and Look at this! drawings (1975), for instance, accentuate the painted line’s wonkiness as the crooked edge of the pages seem to extend directly into and onto the wall [FIGS X, X]. Throughout the show, I wanted to initiate a back-and-forth between looking closely at the interior of a drawing and then zooming out, seeing its relationship to the overall design of the room. In a room of such size, orchestrating this balance between dierent ways of looking and moving through the space was the challenge. Ideally, the drawings and architecture would create a constellation, where all the elements subliminally !re away, leading your eye and body through the space.

A curator may say I approached this whole project backwards, working !rst with the space and second with the objects in the space. But I see it more as a dance than a hierarchy or a !xed order of procedures. I follow this kind of improvisational logic in the studio and all other public spaces in which I’ve curated or created artwork. I am always guided by the materials at hand rather than some predetermined will I have for them—and as a sculptor, my materials necessarily involve the work’s !nal environment, not only the stu in my studio. In this way, I saw myself in service to both

the drawings and the speci!city of The Drawing Center as a site for hanging them, knowing I wanted to create a completely integrated experience of them both. If I was successful, the drawings would stand as autonomous artworks and at the same time create a rhythm throughout the room, inviting a new way of moving and seeing for everyone who encountered them.

The hanging process was necessarily action-oriented, since it all happened in two days. I intentionally came with more drawings than would !t, and I began spacing them out by hanging one piece on one wall and letting that dictate what came next. I quickly discovered that the process of hanging these drawings was the same process as making art and speci!cally the same as making my sculptures. It’s a 360-degree mentality, based on circulating around the object as it comes into being, dealing with all angles at once. It’s the opposite of linear thinking: working from the center outward. This happens not only when producing a single sculpture, but also when working on six or seven sculptures at a time, making moves on each piece, which over time develops a language across the whole group. The relationships unfold in real time. On some level I already knew this, but the experience of diving in at The Drawing Center—taking a leap of faith in the materials’ capacity to create new meaning—confirmed this. As the only artist in the triad of curators, I found myself using the same techniques and strategies I use every day in the studio.

In this spirit, I placed Gaston Lachaise’s Dancing Female Nude with Headdress (n.d.) as the centerpiece of the back room, letting it dictate what followed around it [FIG X]. The !gure’s breasts read

to me like eyes, and from this unfolded the concept of a portrait gallery of sorts. While I did not generally select drawings based on their subject matter, in this room I instinctually developed a hanging strate%y based loosely around this idea. All the drawings are hung so that the sitter’s eyes are at the same height. An imaginary line is thus drawn by their gaze—all except one, the fantastic Stehender Akt (Standing Nude, 1927 28) by George Grosz [FIG X] at the center, #anked on either side by “proper” men—Ingres’s contrite Portrait of Alexis- René Le Go (1836) [FIG X] and Raphael Soyer’s intent Self Portrait and My Father (n.d.) [FIG X]. The portraits are bookmarked on either side by reclining nudes and the incredible pencil drawings by Kinke Kooi that read “Woman” and “Man” [FIG X, X]. The symmetry created by this array of drawings was another way of organizing the space—and also a way to play with the idiosyncrasies of Jack’s collection. I loved discovering this range and a few outliers in what I thought I knew about an artist’s oeuvre.

This back room also posed a unique spatial problem. It is a narrow space, penetrated at its center by an uncomfortably bulky column. A problem is a great thing for an artist, though, usually prompting some idea that ends up de!ning the work. So I played into it, positioning the bench so that the obnoxious column literally “pushes” its center out, turning its formerly straight edge into a jagged one. This created a privileged viewing seat, a perch from which one could address the wall of sitters—speci!cally Lachaise’s “queen,” positioned directly in front of the makeshift throne. The room is full of real personages and opens the notion of what a portrait can be.

Even though a hanging formula took shape in this back space, this is not how I approached the curatorial mandate in general. Like in the process of artmaking, I did not begin with rules, but instead let the drawings speak to me over the course of repeated viewings. It took six months before I even grasped the full breadth of the collection and another eighteen months of coming and going from the collection, pulling out connections between the works. It was a slow burn. Many of the connections were about gesture and mark, not “subject matter” per se. Ray Yoshida’s untitled graphic drawing of parting curtains [FIG XJS276] played o the amorphous strokes of Léon Spilliaert’s L’elevation, which looks like legs parting [FIG X,X]. Further down the wall, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’s drawing, St. Radegonde Taking the Veil, activates the same gesture but in

an explicitly religious context [FIG X]. And !nally, Degas’s literal depiction of legs, Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (c. 1859 60) [Edgar Degas] placed on the register below, makes the gesture even more lucid but never pins it down as one thing—it is still always about the act of drawing. On the opposite wall, Delacroix leads to Darger, which leads to Jim Nutt—a string of artists covering a wide swath of art history and with seemingly oppositional focuses and intentions, yet who are connected by the act of drawing, the act of sitting down and making a mark. What connects Jim Nutt to Cy Twombly is not what they depict, but how they draw: that same nervous but sure hand. In making selections, I kept speci!c meaning from overriding the general attitude of what a drawing is and how the marks are made.

The benches further ampli!ed my overall curatorial strate%y.

I conceived of them as both a place for sitting and a way to bind together the room. The connection is made through color but also through scale as the top register of the painted wall is the exact width of the benches. Of course, a viewer would not be speci!cally aware of this measurement but might subconsciously start to tie the planes together, essentially “#ipping” the #oor up to the wall and the wall down to the #oor. The two registers complicate the notion of an “ideal” viewing height and a single horizon line. Standing upright, positioned close to the wall, the beige line meets the eye at a height of X inches. But sitting down and viewed from afar, the lower register is the one more related to the body, creating a second horizon line.

Nearly all the works hang low in the room, hugging this second, lower register—like a handrail supporting one’s body weight. I imagined the benches to be like logs or tree trunks that had fallen in the forest: nature’s most ingenious, ad hoc form of seating. As such, my carving intervention was actually quite minimal. I left the rawness of the wood intact, making sure that the brutish nature of the outdoors was not lost. I used a range of tools—some creating deep grooves, others shallow—so that every mark was distinct; yet the wood was not completely “tamed” by my hand. I conceived of its surface as yet another kind of drawing mark in the room. I also wanted all sides of the logs to be available for sitting, so I rounded the ends and created divots along the horizontal edges to suggest a seat. This did away with the front/back dichotomy of manufactured benches, allowing a person to reposition oneself along the log in any number of ways. [FIG X]

The benches were made from single, gargantuan trunks of white oak, which were dried for many months. This drying process is a bit like glazing in that there is a necessary surrender to the unknowns of chemistry and physics. While I can always predict how the glazes might chemically react, I ultimately rescind control once the clay enters the kiln and is subjected to heat. In the case of white oak, which I have worked with for many years, I knew its general behavior of checking (expanding and cracking) during the drying process and had a premonition that long, straight lines would form

as the wood expanded and contracted. But I could never know how this would play out exactly. I took joy in witnessing the wood making its own drawing as it cracked. Once I positioned the logs in the room, they created three bold, horizontal strokes, perpendicular to the columns, almost but not quite abutting them. Their straight !ssures played o the more curvilinear contours in the #oor’s !nished planks, and of course the marks across each sheet of paper. Beyond the mark-making, I was drawn to the material synchrony of wood being the precursor to paper. While they are completelydistinct 71 in scale from what is on the walls, the logs created another kind of drawing—initiated by me but beyond my control.

I sensed a similar attitude of minimal intervention in the way Jack has approached his collection. Most of the drawings he has amassed have had past lives and previous owners who framed them and then lived with them. Regardless of condition, Jack has kept most of those frames intact, understanding their relationship to the drawing as a marriage—the drawing and frame: a single complete object. Toulouse-Lautrec’s Le Violiniste Dancla, for instance, with

its nervous, sinewy line, feels intimately related to the peeling frame it sits in [FIG X]. This element was one of the great surprises I experienced while hanging, as my primary encounter with the drawings did not take their frames into account. During my visits to Jack’s collection, I took iPhone photos of the works, which I then printed and moved around like playing cards. The scale and condition of the frames were lost in this process, so it was only in the !nalstage of hanging that they became full objects to me again.

Likewise, I could not know until late in my own process how (or if) Jack’s installation would set the stage for mine. When I walked through his show, I experienced the drawings as autonomous objects—free from the conventional labels that would have placed each work in a certain time period or with a particular artist. Unhampered by art historical tradition, he gave himself permission to “DJ” the drawings according to some other visual logic. I embraced that attitude in my installation but made it more spatial. I felt compelled to deal equally with the architecture and the drawings so that all the elements—the walls, the #oors, the columns, the drawings—would be experienced as an inevitable choreography, each part inseparable from the next, much like the original frame is to the drawing it holds.

In the end, as Hilton Als suggests in his essay in the first volume of this publication, it’s all about love. Over and again, I fell in love with each piece I hung and so many others. Each of these artworks, one way or another, is about life with love, and the collection itself is now more alive than ever, having been seen and jostled by the three of us and swooned over by those who visited the shows at The Drawing Center or turned the pages of this book.