Full Steam Ahead - Artist Statement

By: Arlene Shechet

Download PDF

As a sculptor with a perfectly reasonable career showing in galleries and museums, I had to ask myself why I felt the urgency to place work outdoors, and in a public space. After many site visits, I envisioned a project where chance encounters, changing conditions of weather and light, and unpredicted activity would all become integral to the actual sculptures—using these elements as materials in their own right. Most previous installations at the Park have taken place at its center, on the central green. I decided to move off center and not simulate an exhibition environment where the works are kept at a distance, but rather create a body- to-body experience with the work: to capture people’s imaginations and surprise them. Without seeking an art experience, passersby would suddenly find themselves in the middle of an installation. This seemed like the hardest thing to do. Why not do the hardest thing, on the hardest surface?

I followed the foot traffic. On the north side of the Park, stone pathways encircle a pool. I saw this circular form and its radiating paths as preexisting conditions that I could bring new awareness to (fig. 8). Mining the architecture of the circle—recurrent in my work—I saw it as a found mandala, a natural site for circumambulation, a radiating star, a sprue that feeds from the center outward to surrounding paths, streets, the city. This northern terrain also has a natural gradation to it: a series of “step-downs” from high to low. At the apex is the monument of Admiral Farragut, which leads downward to the reflecting pool. My first gesture was to endorse the seasonal draining of the water from this pool, making it an even deeper base. The sidewalk dropped to new ground, creating a vessel. Now empty, the circle became a bounded space for gathering people, and the rim became available for seating. This idea of a sunken living room or “conversation pit” was akin to memories of my grandparents’ sunken living room in their Bronx art deco apartment, and the Dorothy Draper– designed restaurant at the Met, which I frequented as a child. Within this invented outdoor room, I resolved to make a family of sculptures, a group that would question the notion of the “monumental.” The works would be human-scale, touchable, resonant, and yet not entirely knowable.

The notion of “delight and discovery” soon took hold as a driving idea. I understand this eighteenth-century concept associated with what we now call relational aesthetics—the idea that the audience experiencing the work becomes a part of it, is awakened by it, and actively participates in its meaning. In all of my installations, I have listened to the space and tried to draw attention to the elements that people may otherwise ignore. The installation prompts a discovery of the “less visible” as different populations encounter it by chance, in unpredicted ways, which are out of my control as the artist.

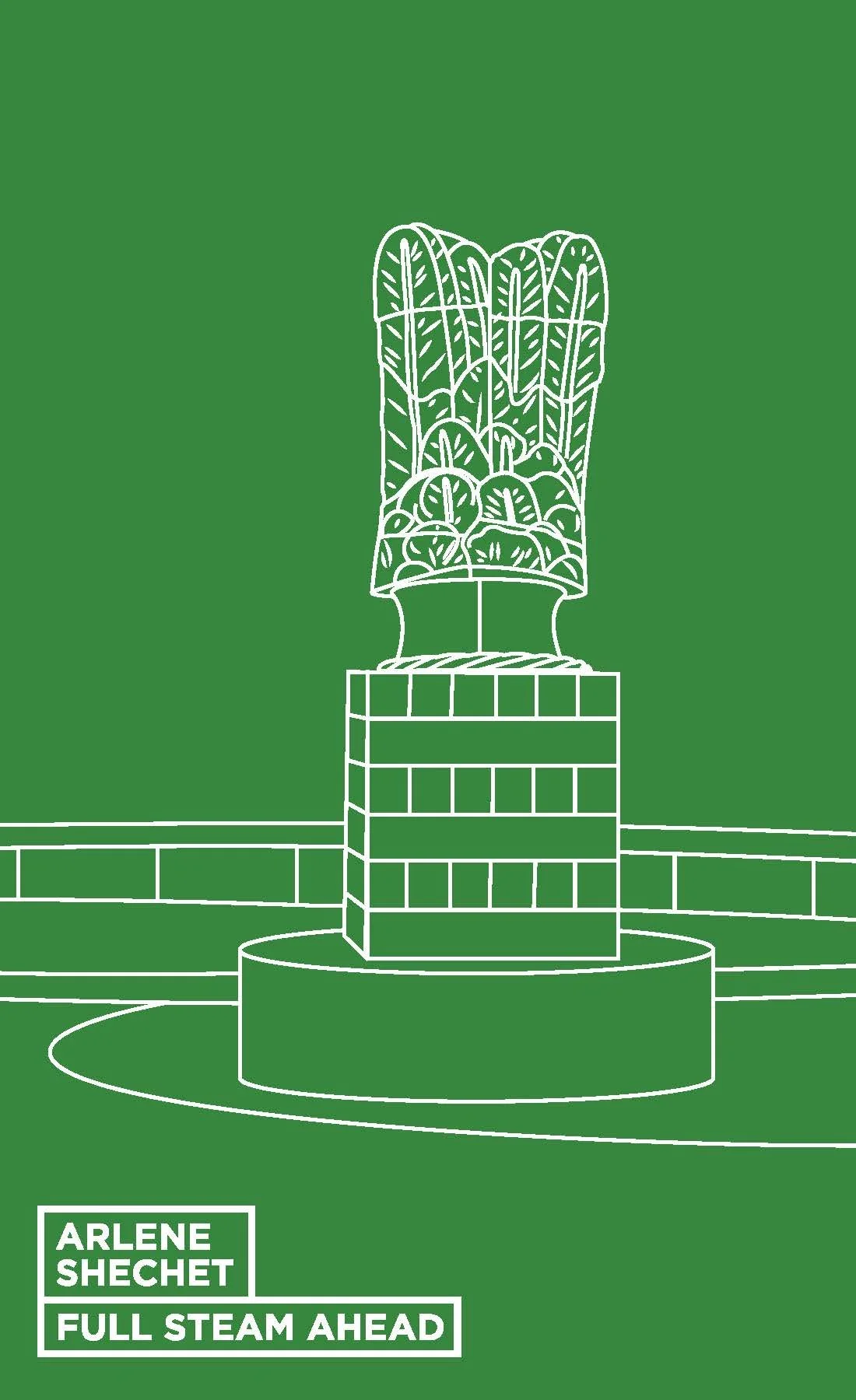

The imagery of the sculptures evolved from my time at the Meissen porcelain manufactory in Germany. There, I had made a series of miniature porcelain “sculpture gardens” using painted plates as landscapes. I saw a parallel between their circular form and the empty reflecting pool of the Park. Parts of these small sculptures became models for the installation, to be reimagined at human scale: a lion’s paw as a boulder (Kandler to Kohler), a low-hanging cloud that could be seen as a giant lion’s head, and “teacup handles” that reach the proportion of Admiral Farragut’s bent arm. In a loop of meaning, these curled handle-like shapes return to the outdoors to regain their references to birds, flowers, and leaves. The most monument like of the sculptures is a large bird feather (Tall Feather) that stands upright on stepped plinths. In addition to the large sculptures, the installation contains quieter gestures that further encourage surprise and discovery: pigmented resin bench slats (Threads), electroplated reflective tiles (Ghost of the Water), and fanciful table-seats (Skirt Seats). Because these elements are multiples, existing in more than one place, they create a continued language of repeated noticing.

I had first used porcelain outdoors in my 2016 Frick installation. In the tradition of gardens at Meissen and Versailles, I placed large Meissen porcelain animals in the Frick’s garden. At Madison Square Park, I took this gesture one step further. I enlisted the Kohler corporation as a collaborator, because the rarefied language of porcelain finds its way into daily life via the manufacture of bathtubs and sinks at Kohler in Wisconsin. Moving from Meissen in Germany to Wisconsin permitted me to transform a material that is marginalized as “fragile and female” into something that is “monumental,” durable and resilient. At this scale, the interior language of the decorative arts becomes reinvented for the outdoors. It is Forward, a full-bodied hand-carved wooden figure, that grounds the monument area. She sits on the steps below the bronze statue of Admiral Farragut. Constructed like a boat, she anchors him. Unlike Courage and Loyalty (nineteenth-century female allegories carved in the granite below him), Forward represents a real, non-nymph woman. So named for her determination and resolve, she sits with her body pivoted toward the allegories, but she gazes ahead. This non-white wooden figure is at one with visitors sitting on the existing steps. Channel Liberty (with Fallen Arm) is the installation’s other female presence, broadcasting an association with the Statue of Liberty. The left arm of Lady Liberty holds a symbolic Declaration of Independence, but in my sculpture the arm is fallen in distress. All of the sculptures are intended to have many readings; in this case, I hope also that Channel Liberty recalls the fact that between 1876 and 1882 the torch and right hand of the Statue of Liberty were on view at Madison Square Park.

Passersby, adults eating lunch, children playing on the sculptures—these people activate the site every day. But I also wanted to curate a series of live performances to further utilize the pool as a classical amphitheater, a gathering place. The circular form of the pool creates a situation in which people view the performers and one another across the circle. This creates community and a sense of shared joy.

My collaboration with Dianne Wiest realized this idea. As she performed excerpts from Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days during five consecutive lunch hours, visitors would hear these free-floating words as they walked by. The fractured language of Beckett aligned with the public’s passing movement. Jonathan Kalb recalled John Cage, who “envisioned a continuously running event that people drop in on at will, that blurs the boundaries between art and life.” Notably, there was “no prefatory fanfare, no curtain, no stage, or framing gestures” which would have isolated the performance from the fabric of daily life. With Beckett, each line is the whole story. This concept is an entry point into the installation: each sculpture individually contains the project’s complete vision yet may also be experienced on its own terms. The other programs I’ve organized—talks with artists, spoken word and musical performances—will take a similar form, weaving through the space seamlessly.

My studio work has improvisation at its core. But in this case, the improvisation extends to external conditions such as weather, sunlight, the seasons, and wonderfully (mostly) unpredictable humanity. This is terrifying and thrilling. The project’s evolution is out of my control and its meaning is indeterminate, contingent, and fluid. In its open-endedness it embraces the everyday and the facts of being alive. I join the ranks of observer with delight and wonder.