Introduction

By Brooke Kamin Rapaport

Arlene Shechet may be best known for realizing work in ceramic, a material associated with brittleness, fragility, and its application in vessel making. Since the 1980s, she has shattered that hoary association by producing transcendent sculpture with unanticipated form, surface texture, and dynamic color. Her work often alludes to the folds, limbs, and crevices of the human body, and she plays on and cues the viewer’s willingness to imagine. In keeping with its relation to the body, she typically makes human-scale work. So with the prospect of her first major outdoor public art project, in Madison Square Park, Shechet had to solve some problems.

She exploded the scale of her sculpture not to the colossal, but to larger than life. Porcelain became her material of choice for the outdoors because of its durability. A 2017 residency at Kohler in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, enabled her to work with the same porcelain used for mass-produced toilets and sinks, yet she brought her distinct visual language to the material while enhancing the scale for outdoors. And a collaboration with Porcelanosa allowed her to introduce cast resin, in the form of a material called Krion, to the bench slats and seats on Park benches. Shechet also made new work for this project in steel, electroplated tiles, and wood.

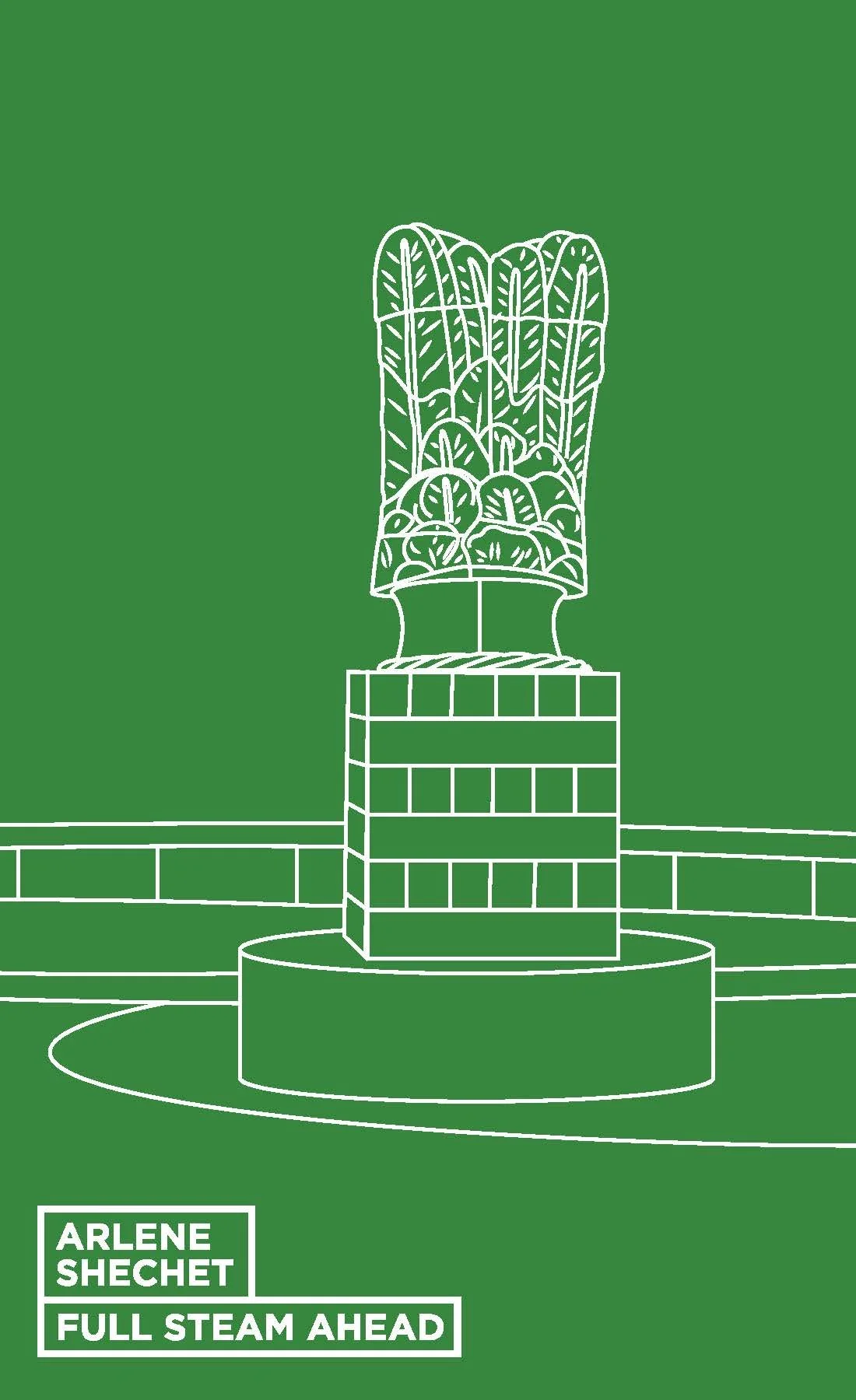

Her initial gambit may have been inspired by witnessing puddles in the Park’s drained reflecting pool. Shechet photographed those shimmering memories of a rainstorm and went on to install one hundred mirrorlike tiles on the ground plane of the pool, a constant reminder of the ephemerality of a vision, and of the dwindling of a natural resource. Tall Feather and Low Hanging Cloud (Lion), both in white porcelain, also nod to environmental concerns: the feather hoisted onto a platform like a trophy of a bygone era, the lion head a flashback to the power of a mighty beast. Shechet’s trees (which she calls sprues, a reference to the channel through which a liquid substance is poured into a structural mold) have no leaves and look like splayed, defiant human arms. No factor in this man-made amphitheater has escaped Shechet’s gaze, including the dominant presence of Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, the Civil War–era Union Navy hero who presides over and above the space where Full Steam Ahead is installed.

The Admiral Farragut Monument, dedicated in 1881, was a collaboration between American Renaissance sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Gilded Age architect Stanford White. The Farragut sculpture was considered vanguard in its day for the figure’s naturalism, conjuring the admiral’s steady stance on the prow of a ship, his coat flapping open in the breeze. With recent and controversial attention paid to historic monuments across this country, Shechet knew that Farragut’s prime position as a male commander must be addressed. Because the project is on view across the seasons, from fall through winter and into spring, she worked with a lighting designer to sensitively spotlight the darkened monument each evening. Her critique of Farragut’s permanent bronze presence involved the installation of a temporary wooden seated female figure, titled Forward (fig. 3), more modernist form than nineteenth- century comportment. Seated on the monument steps, she plays against—or to—Farragut.

Shechet’s Forward is of two worlds: the figure becomes part of history by her presence and her outsize stature, but dips a toe into the hardscape, firmly planted in the here and now. Farragut’s call to his fleet during the 1864 Battle of Mobile Bay—memorialized as “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”—is a reference point for Full Steam Ahead. It grounded the artist, who pushes her work to the edge of irony, materiality, and humor.

Fig. 3

And it has hastened Parkgoers, whose charge toward constant motion has been stopped by this project, an outdoor place for sanctuary and for joy.

In a sort of pas de deux, Shechet conceived Full Steam Ahead as an outdoor room, while from a curatorial perspective the project might be characterized as an outdoor sculpture court. The two descriptions—one suggesting intimacy, privacy, personal interaction; the other focused on publicness, commonality, community— exemplify the complicated tension and culminating balance in the interpretation of public sculpture and of this work specifically. Both descriptions are right, for both privilege valid conceptions of what it means for sculpture to come out into the public realm.

For Shechet, the goal for an outdoor room created through her work was to bring informal interplay to the Park’s hardscape, terrain most frequently used for urban access from east side to west. She describes how the Park pathways channel people’s movements and refers to how individuals are funneled through their daily commute, in a manner recalling the branches of her work. The Park’s reflecting pool, and its annual seasonal draining in particular, lingered for the artist, who remembered the sunken living room in her grandparents’ apartment on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, which paralleled the below-grade reflecting pool and its circularity. Shechet’s work surrounds this water feature, but it is empty, with only a reflection of the abundance that was once in the pool.

Alternatively, the rough-and-tumble civic sculpture court—open to all in a site teeming with people— shatters the preciosity of traditional indoor sculpture court settings, where quietude and contemplation guide behavior. The sculpture court is a reminder of Shechet’s 2016–2017 exhibition Porcelain, No Simple Matter: Arlene Shechet and the Arnhold Collection, at the Frick Collection in New York. She was the first living artist invited to assess a historic body of porcelain, the promised gift to the Frick from collector and philanthropist Henry H. Arnhold. In that project, she selected eighteenth-century pieces from the Royal Meissen manufactory and juxtaposed them with relevant examples of her own work. Even the quietude and hush of the Frick’s Portico Gallery, where the works were on view, echoed the traditional sculpture court, which the artist upended by thrillingly showing her contemporary sculpture cheek by jowl with the Meissen porcelain.

In Madison Square Park, Shechet’s objects become transformed stand-ins for the expected works in a museum sculpture court, conceptually and formally altered for the outdoor setting: ancient heroic nudes in marble and Renaissance busts of prominent citizens, often with a central flowing fountain, are nowhere in sight. Instead, Full Steam Ahead allows the quotidian to become sculptural: seating areas, natural forms, and suggested body fragments are refreshed, and these objects compel us to look again.

So why would Shechet—whose 2015 exhibition All at Once at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, whose show at the Frick, and whose 2012–2013 residency at the Meissen porcelain manufactory in Germany all confirm her stature as a prominent sculptor of an unsung material, clay—want to make her work vulnerable outdoors? The opportunity to place her sculpture (and to add materials in addition to porcelain) directly within the walking paths and traverses of a site where people have direct physical contact is the guiding force. Shechet’s work has always teetered between the dissolving distinctions of figuration and abstraction, representation and non-objectivity. In museum exhibitions and in gallery shows, her work conjures restless, unpredictable allusion to nature and the body. Pushing her sculpture outdoors into a park where choreographed nature and throngs of people are hustled together clicks as a vision for public art.

It is a bold move. Shechet was the youngster in the list of twentieth-century American artists most closely associated with freeing ceramics from its long-standing connection with vessel making and with legitimizing it as a material for investigating critical issues in sculpture, such as surface texture, color, corporeal content, and the obfuscation of three-dimensionality. Ron Nagle (b. 1939), Ken Price (1935–2012), and Betty Woodman (1930–2018), for instance, each pursued questions beyond modernism in their work. Shechet stands between these artists who came of age confronting the former reigning movements of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism and a new generation of artists who have taken on ceramics with an unexpected bravura of independence, artists such as Julia Haft-Candell (b. 1982) and Sterling Ruby (b. 1972). Shechet, Phyllida Barlow (b. 1944), and Vincent Fecteau (b. 1969) are receiving increased attention for the physical beauty of the sculptural surface, the disregard for any preconceived limits in materials, and for tossing off the regimented and outmoded category of abstraction.

Perhaps Shechet’s first venture in outdoor sculpture will be the opening gambit for others to propel their work into publicness. It’s an unforeseen move for a ceramic artist, but not surprising for Shechet, whose role as a disrupter is central to her work. At its core, Full Steam Ahead has transformed the north of Madison Square Park into a populated zone where Parkgoers fulfill her goal to physically circumnavigate the site to study her work and to idle giddily, sitting on the edge of the emptied reflecting pool, on striped benches, or on resin Skirt Seats. On a recent fall day, adults rested on the ottomans, children played near a white porcelain memento of a bird’s wing, and extreme yoga practitioners trained their poses to mirror her sculpture.

Shechet has augmented the delight of happenstance by conceiving public programs and activities: performances of Samuel Beckett featuring actor Dianne Wiest, a voter registration drive for the midterm elections, and poetry readings and conversations during the months her work is on view. This is complete fulfillment of the artist’s plan to sanction urban moments when joy has unabashedly and unexpectedly crept into public art.

Like all of Madison Square Park’s exhibitions, Full Steam Ahead could not have been realized without the extraordinary support and counsel of the Conservancy’s Board of Trustees, including Board Chair Sheila Davidson. Our Art Committee, chaired by Ron Pizzuti, is a group of thoughtful advisors who share their guidance, generosity, and wisdom. We are grateful to Christopher Ward of Thornton Tomasetti, who worked with the Conservancy and the artist. Our neighbors at Porcelanosa—Manuel Prior, Carlos Monsonis, and Sindy Guerrero—have shown unstinting generosity to the project and to Shechet’s vision. At Kohler, Shechet was guided by Amy Horst and Kristin Plucar. Our thanks to Marc Glimcher, Susan Dunne, and Adam Sheffer at Pace Gallery for their wonderful support. At Madison Square Park Conservancy, Tom Reidy, Senior Project Manager; Julia Friedman, Senior Curatorial Manager; and Tessa Ferreyros, Curatorial Manager, have been outstanding colleagues on all aspects of this project. In her studio, the artist was assisted by Eric Ehrnschwender, Jessica Gaddis, Chelsea Maruskin, Pareesa Pourian, Johnny Poux, and Julia Rooney. Linnaea Tillett at Tillett Lighting Design has added a subtle nightscape to Full Steam Ahead. Thanks to Carter Foster at the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin and to Lilian Tone at the Museum of Modern Art in New York for their thoughtful and perceptive essays in this volume. Arlene Shechet has always proceeded full steam ahead. We congratulate her for bringing her significant work to Madison Square Park.