Rococo Redux 17

By Carter E. Foster

Arlene Shechet’s deep curiosity about the nature of materials drives much of what she does. Her sculptures in ceramic, porcelain, and clay—favorite mediums—may be hard and still, but they often appear soft and in the process of forming, morphing, or becoming. In recent years, her interest in porcelain’s European history, specifically at the Meissen factory in eastern Germany (where she had a residency in 2012–2013), have led her to explore eighteenth-century traditions and the style of art known as rococo, which flourished in that period. Shechet has also recently engaged museum spaces and collections using her own work in several exhibitions—at the RISD Museum (2014), the Frick Collection (2016–2017), and the Phillips Collection (2016–2017). In the first two she installed historic Meissen objects alongside her own creations from that factory. The Madison Square Park project provided her quite a different platform of expression, not indoor museum galleries but a public, urban outdoor space in which spectators can move around and physically interact with a holistically conceived array of her work. And rather than having to respond to fragile, carefully protected historic art objects and the tropes of museum display, Shechet had the history of landscape architecture and large-scale public monuments with which to engage. Madison Square Park features an 1880 bronze and black granite monument to Admiral David Glasgow Farragut by sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and architect Stanford White. These men, two of the most prominent artistic personalities of their time, collaborated on the monument, one of the first by Americans to manifest the art nouveau style (itself a descendant of rococo). It memorializes both a prominent figure and a prominent moment in American history. The admiral’s command against Confederate ships at the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864—famously paraphrased as “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”—has indeed gone down in history, and it gave Shechet her title. Despite the physical scaling up of her own work in response to the site and its statuary, the artist did not move away from her rococo interests but found a new way to explore them.

Parks and gardens underwent a transformation at the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth, shifting from the grand, formal, rigid geometries epitomized by French landscape architect André Le Nôtre’s gardens of Versailles to more intimate, human-scale spaces. Antoine Watteau’s paintings illustrate this change, celebrating small pockets of nature in which human beings, statuary, architecture, and plants offer areas of fantasy and reverie (fig. 13). The rococo aesthetic is typified in part by the merging of nature and ornament, in some cases producing completely artificial garden spaces, often expressed most fully in the graphic arts and in the decorative form known as the arabesque.1 In an etching by Gabriel Huquier after Watteau, The Temple of Neptune, for example (fig. 14), a slice of earth with a shallow, stagelike perspective provides a base for fountains, statues, and mythological creatures. As is typical of this particular strain of the arabesque form, the relatively realistic space, architecture, and statuary in the center of the composition intertwine and dissolve into abstract ornament, stylized vegetation, and flattened space as one moves toward the perimeter.

Another rococo print helps us understand how ornamentation, architecture, statuary, and people could coalesce in both the real gardens of the eighteenth century and the artificiality of an arabesque. It is a fascinating image to compare with Shechet’s rococo preoccupations in the twenty-first century. Charles- Nicolas Cochin’s depiction of an actual event, the fireworks presented in 1735 for members of the royal court in the gardens of Meudon, a château outside Paris, is a kind of arabesque come to life in the real world (fig. 15). This “illumination and fireworks” given to honor the Dauphin of France on his birthday is frozen and stylized in Cochin’s print, but nonetheless the depiction is likely fairly accurate in recording how the event looked, the temporary decorations and architecture designed for it, and the fashion and comportment of the attendees. Here is a real—if removed, aristocratic, and coddled—world of leisure populated by known people in a specific place, depicted in a graphic language that merges the artificiality of the ornamental arabesque with garden theater as it really happened.

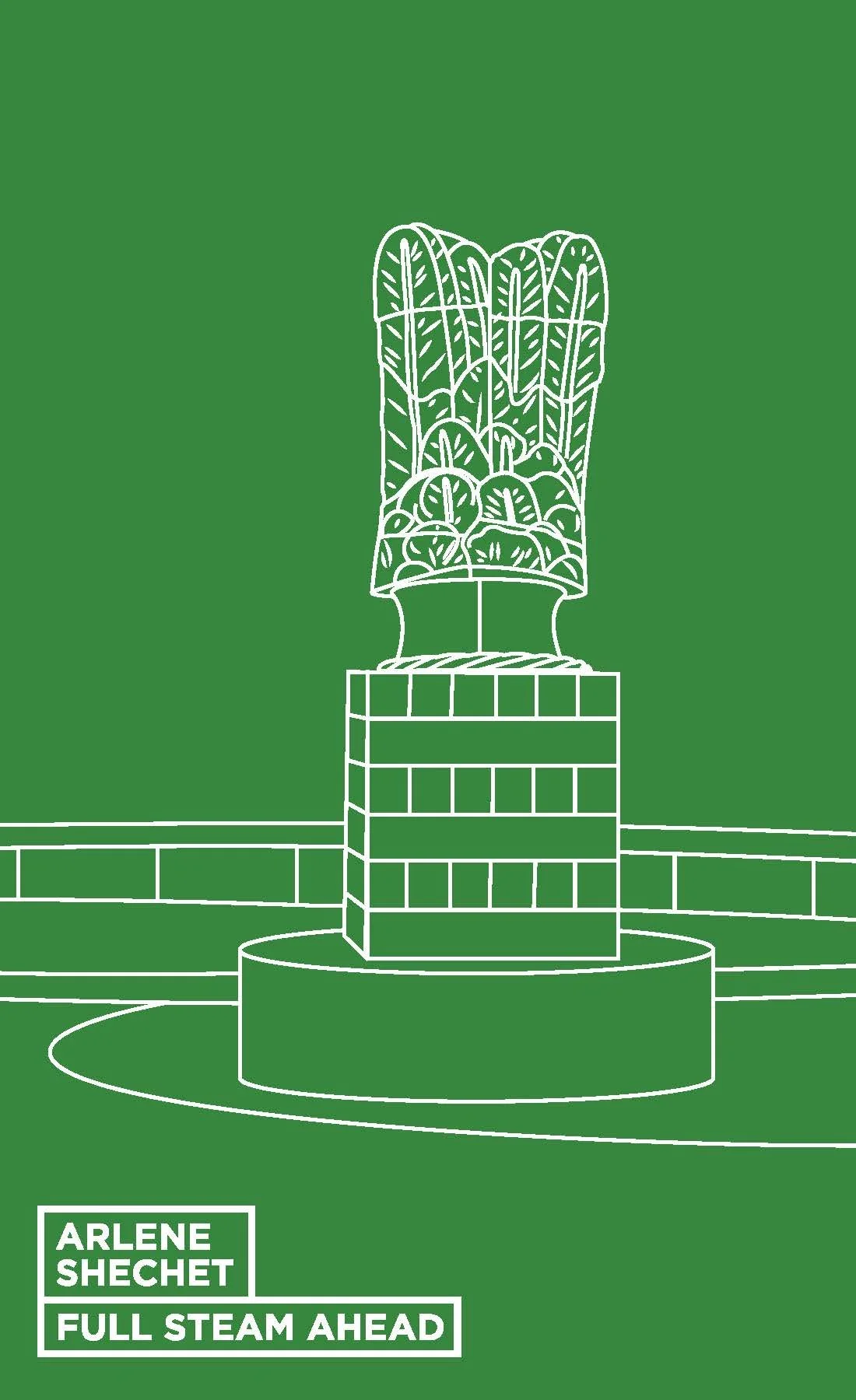

Visitors to Shechet’s Madison Square Park interventions may or may not be finely dressed aristocrats, but they similarly interact with human-scale garden sculpture, activating works in a specifically conceived and defined setting. Gardens have long been sites of fantasy and theater, producing an atmosphere of play and leisure by combining architectural, ornamental, and allegorical languages (especially true, historically, when they were sites for temporary festival structures). With a mix of plantings, statues, fountains, and architecture, eighteenth-century landscape designers often composed outdoor rooms, also known as bosquets or cabinets de verdure. When Shechet was thinking about how to approach the Park site, she focused on the circular fountain area in front of the Farragut monument, the fountain itself the center of a larger circle where six of the Park’s walkways converge. In traditional bosquets, fountains with statuary are often the focal point of the space, a kind of centerpiece around which people can stroll or sit. Shechet endorsed the seasonal draining of the pool, because even dry,

it could still function as a focal point, giving her a concentrated and defined area in which to place her work. Furthermore, it allowed her to respond and effectively appropriate the existing monument into her own installation. This parallels the history of temporary festival design in European gardens, in which permanent statuary might be incorporated into the iconographic program or decorative compositions of festival design.

Shechet’s chief rococo inspiration here is of another sort, however, than the delicate language of the arabesque and the rocaille (rock and shell) motifs that typify its most common ornamental language. The rococo was also a golden age of the small-scale porcelain figurine and of astonishingly hued and elaborate ceramic table settings; the Meissen factory in Germany and the Sèvres factory in France were the two most famous manufacturers of such objects. The artist’s work at Meissen, at the RISD Museum and the Frick, and later at the Kohler manufacturing company in Wisconsin (perhaps best known for its porcelain plumbing products) primed her to deploy her mastery of the material but to scale it up hugely. Her bosquet concept is clear in an early working collage (fig. 17) in which she began figuring out the placement of her objects and establishing their relationship to the Farragut monument, to one another, and to the circular space and the paths leading to it. While at Meissen, Shechet had also begun a series of miniature sculpture gardens that riffed on the platter form as well as the object known as a deser—a whimsical and elaborate table centerpiece that took a variety of forms, sometimes architectural, and often with porcelain figurines (fig. 16). Looking at one of these is like looking into a mini imaginary bosquet from above, and they perfectly encapsulate the idea of an outdoor garden room as a site of decorative fantasy. Full Steam Ahead became a logical— if much-enlarged extension—of the artist’s neo-rococo plates, and functions in some ways like a life-size deser in which the figures are the real people who circulate in and around its objects.

As with her work at Meissen, the formal language Shechet chose to explore for Madison Square Park took its cues from sculptural processes. The objects she had made in Germany employed the forms of the many historic molds still in use at Meissen. Back in New York City and Kingston, New York, where she rented a large studio to work on Full Steam Ahead, the shape of the sprue began to interest her. A sprue is the channel through which liquid medium is poured into a sculpture mold, and Shechet relied on its sinuous form for several of the large pieces in the Park. The curves and countercurves she fashioned with them are, broadly, also fundamental to the curling scrolls of rococo’s basic decorative language, and hark back as well to arabesque lines typical in classic French garden parterres through patterned plantings. Deploying porcelain as she does here completely turns tradition on its head, using a material associated with delicate, precious, small objects for big, bold things people can, and are in fact encouraged to, touch. The sensuousness of the material’s smooth, hard surfaces generously invites the viewer to haptically test the forms, without breaking any rules or putting the pieces in jeopardy.

The visitor who fully explores the space Shechet has defined here may eventually come to settle naturally in the center of the dry fountain, adjacent to the set of reflective tiles set into its bottom called Ghost of the Water. This seems the ideal vantage point for taking in all of the sculptures together—one can rotate in place and see almost every element—and understand how they frame and co-opt the Farragut monument. For, in addition to the fantasy and garden play of the rococo, Shechet probes the idea of the public monument, toying with its traditional, patriarchal seriousness. In Cochin’s fireworks print, allegorical gravitas in the form of Hercules slaying a dragon is in the center of the airy, filigreed lightness of a rococo decorative ensemble. In Full Steam Ahead, Farragut and his allegorical female attendants below, Courage and Loyalty, no longer dominate their circle but seem to be set free to play with their temporary mates. Shechet’s wooden seated female figure Forward becomes like a third allegory to the admiral and also seems to refer to statues like the Little Mermaid in Copenhagen (and its progeny around the world), allowing us to imaginatively reinterpret Farragut’s relationship to the sea. Nodding to the role monuments and statues play in establishing and embellishing historic and nationalistic narratives, Shechet gives us prompts, tools for creating our own stories. Her lion’s head is, for instance, very much part of the lingua franca of monuments in Western art. In New York, it resonates with Patience and Fortitude, the feline allegories who famously guard the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue. But it could also be many other things. The other recognizable elements in Shechet’s garden—a bird’s wing, the lion’s disembodied paws, a monumental feather, a piece of rope—may suggest to us other aspects of the American story, or of those told throughout the world in the language of sculpture and allegory. However, their meaning is left unfixed, just as the meaning of any monument will change over time as new histories and contexts emerge. Here, contemplating Shechet’s array during the run of Full Steam Ahead, our minds are joyously free to play for a bit, as one should in a park.